The Urgent Need to Transition From Fossil Fuels

For decades the vast majority of our energy requirements have come from the various types of fossil fuel stored underground, known as hydrocarbons (HCs). Learn more about energy here.

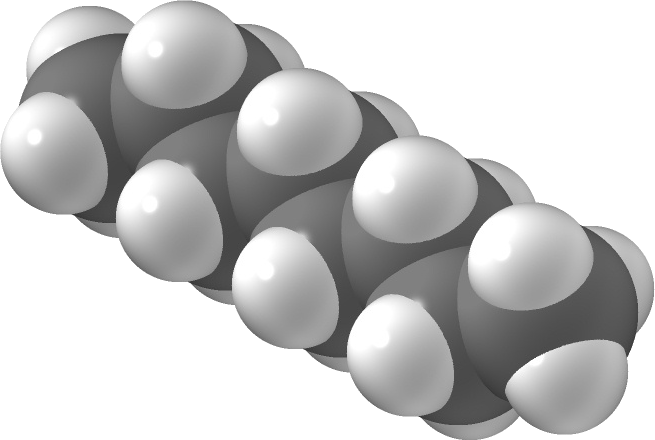

Depending on the molecular mass, these carbon-hydrogen molecules are gases such as methane, ethylene or propane; or the number of carbons exceeds 5, these compounds are liquids including hexane and octane.

Although these fuels are conveniently and economically extracted from the ground, the continued combustion of these HCs in the presence of oxygen (O2) and nitrogen results in the formation of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide (CO2) and various nitrous oxides. If the HCs are contaminated with sulfur, then sulfurous oxides are also formed. When climate conditions are right, mass accumulation of these gases results in toxic smog and air pollution, which is now recognised as a major contributor to disease and death in urban areas.

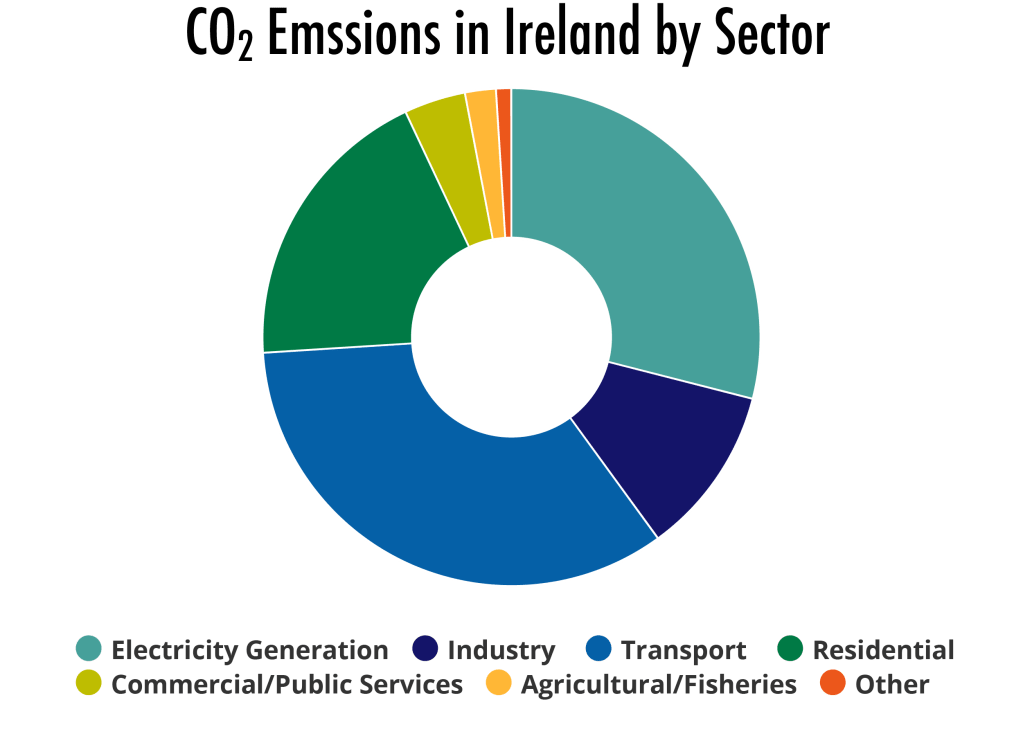

Combustion results in carbon dioxide, one of the oxidation products, but particulate matter (PM) is also generated. These nano-sized particles of various sizes (2.5 nm, 5 nm and greater) are responsible for significant lung damage, especially in urban environments. CO2 is a strongly infrared absorption molecule and is responsible for altering the Earth’s solar thermal balance. In Ireland, the greatest emissions are from the transportation sector. Hence the decarbonisation of the energy storage employed by vehicles should be our highest priority.

Part of the solution is hydrogen and water.

Properties of Hydrogen Gas

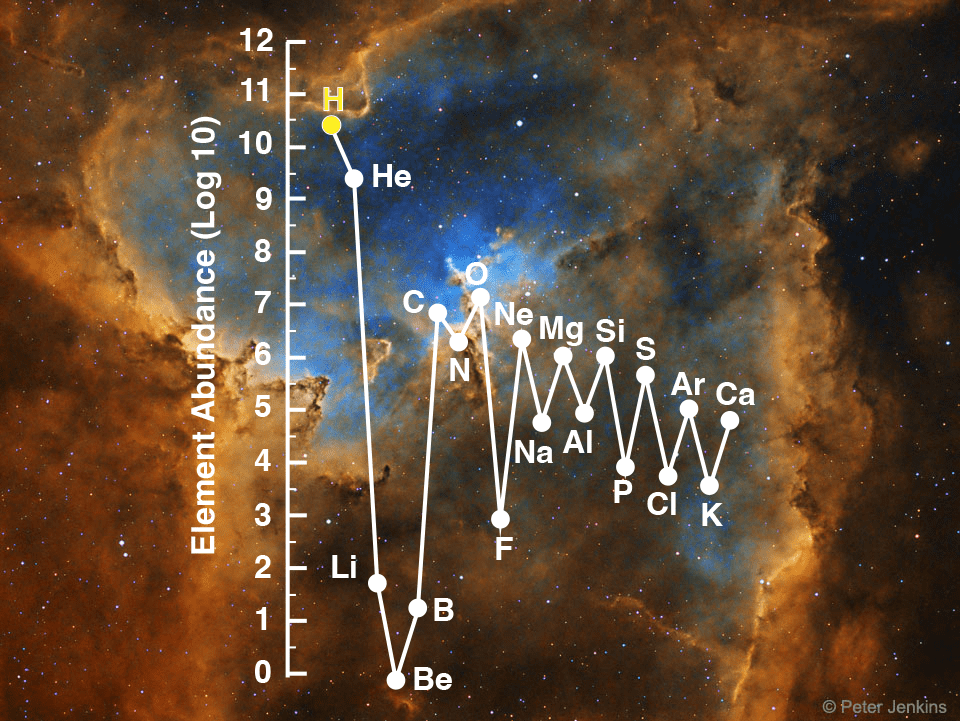

Hydrocarbons such as octane feature highly energetic bonds, but carbon is roughly 12 times heavier compared to hydrogen, the lightest and most abundant element known.

Hydrogen gas (H2) is simple but highly energetic molecule. It is most abundant molecule on Earth and in the known universe. However, molecular H2 is a light weight gas which is lost from the atmosphere.

At present, H2 is stored in thick-walled steel or carbon fire composite cylinders. The small size of H2 can, over time, enter small fissures in the surface and cause embrittlement, weakening the container material and compromising safety.

.

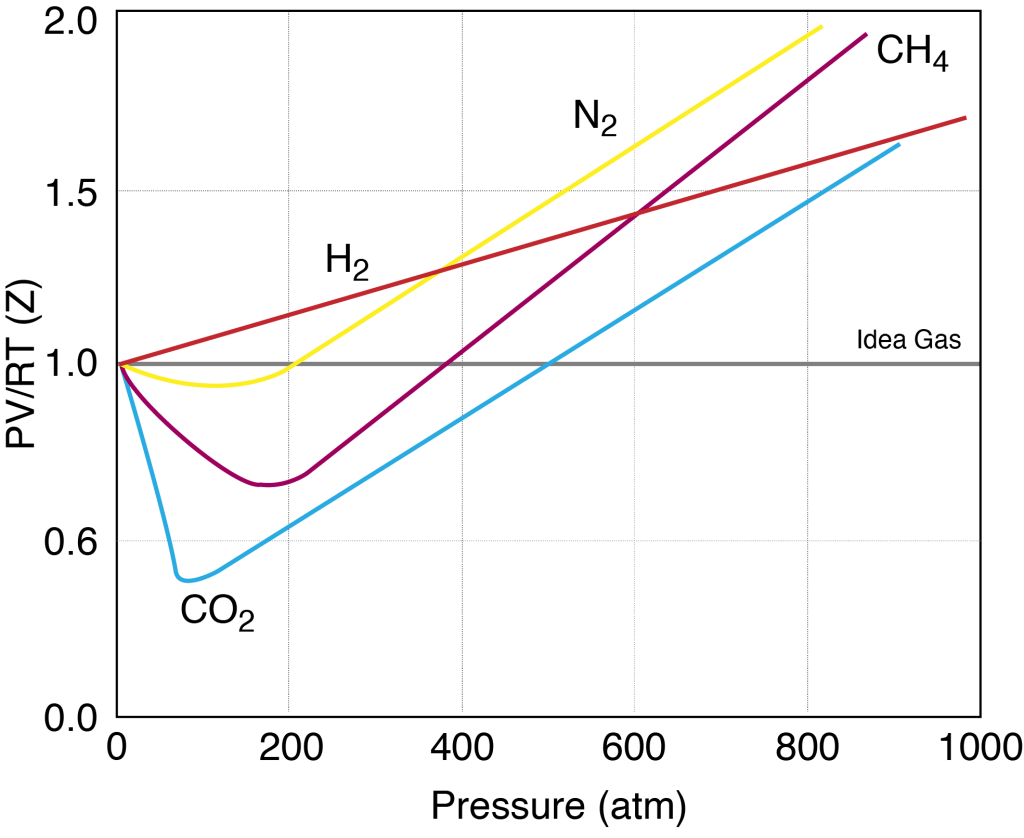

An additional problem with H2 is the lack of compressibility (Z-factor) normally associated with other gases such as N2, CH4 or He.

Hence there is a limit on the amount of hydrogen gas that can be stored within a gas cylinder at ambient temperatures. Organisations such as NASA store hydrogen as a liquid at cryogenic temperatures, but this method is not practical for small applications.

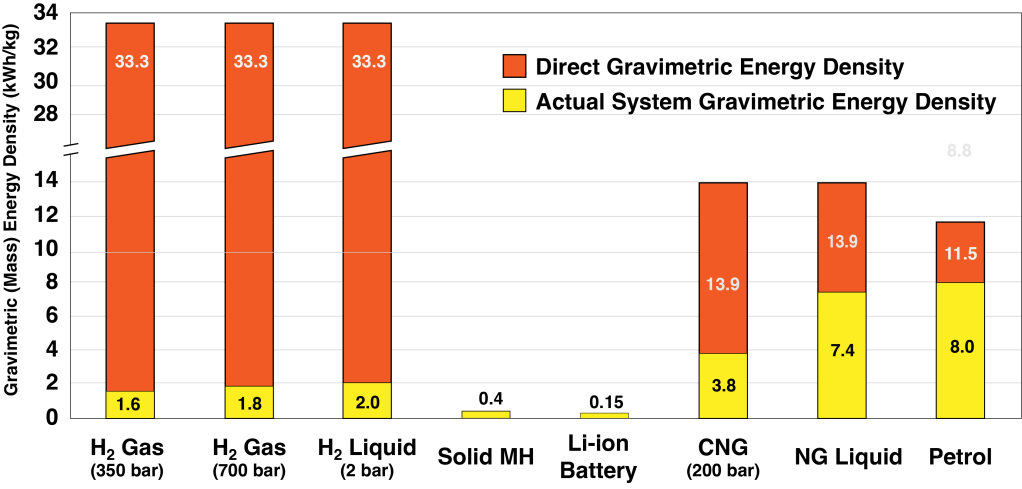

One key aspect of hydrogen gas is the high amount of energy contained in the H-H bond relative to its light molecular mass. This results in a high gravimetric density compared to natural gas and petroleum and significantly higher than Li-ion batteries. However, the main problem with hydrogen is what is termed the system weight which in this case are high weight of the steel or composite gas cylinders.

Nevertheless, H2 is typically stored at pressures of either 350 or 700 bar with the volume dimensions restricted to the particular application.

- Insert Info about the Murai

The goal of this project is to develop a safe alternative for storing hydrogen with both favourable volumetric and gravimetric densities..

Safety Concerns around Hydrogen

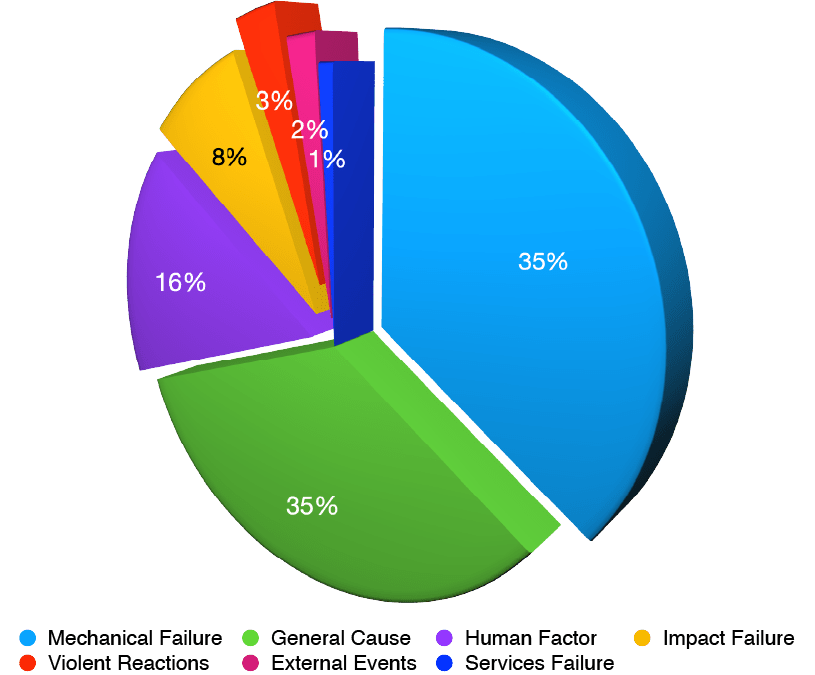

Although hydrogen gas has excellent potential to store high amounts of chemical energy and efficiently convert it into electrical energy, considerable challenges exist for its large-scale deployment. The highly flammable and explosive nature of H2. The explosion during docking of the airship Hindenburg with 35 fatalities was an early lesson. However, more recent accidents have raised serious concerns about the use of hydrogen, and several academics and NGOs have been tasked with developing robust protocols across numerous applications. A survey of 118 hydrogen-based accidents1 by Gerboni revealed that the major cause is a mechanical failure or human error. However, the cause of many accidents were not provided or determined.

Hydrogen gas forms explosive environments within a range of 4 to 75%. The force generated by a hydrogen explosion is high as measured by a deflagration index of 550 bar m/s, versus a lower 55 bar m/s for methane. Therefore, the destructive potential of a H2-based explosion is very high.

The flame velocity of a H2-based fire is also extremely fast (300 cm per s) compared to cNG or methane (30 cm per s).

A hydrogen-based explosion at a US power plant.

The extremely low ignition energy of hydrogen (0.02 mJ) versus methane (2.80 mJ) indicates a high proportion of H2 leaks result in a flash fire with uncapped leaks affording highly dangerous jet-type flame, where a 14 mm hole produces a 1.7 m long flame.

Therefore to migrate the risks and hazards of storing liquid or gaseous hydrogen is incorporate hydrogen within a chemical framework and release only the required amount of H2 gas for conversion into electrical energy and water.

Goto the Ammonia Borane page.